Shoulder problems may not be the most talked-about condition in Gaelic Football and Hurling. Most of us are more familiar with cruciate knee injuries or groin problems. However, shoulder problems are among the more common of GAA injuries with the reported incidence in the literature for shoulder injuries been approximately 17-19 % of all GAA injuries.

Shoulder dislocations, in particular, can be serious and can result in up to 6 months out before returning to sport. Due to the joints construction and the demands placed on it in a contact sport, the shoulder has a high recurrence rate of dislocation. Studies have shown that the recurrence rate can be as high as 29% post keyhole surgery in collision sports.

If a player has sustained an injury in one shoulder they are at higher risk of sustaining an injury on the opposite side. Repeated dislocations can rob athletes of valuable playing time and negatively influence performance. However, with early and appropriate management players can make a very efficient and successful return to sport following shoulder dislocation.

Common mechanisms of injury for a shoulder dislocation in Gaelic games include the tackle, gathering possession overhead, falling onto an outstretched arm, the shoulder tackle and collisions.

Understanding the shoulder and the demands placed on it in football and hurling can help prevention, faster recovery times and reduction of overall injury rate. The purpose of this article is to guide players through the management options available following shoulder dislocation. More importantly, it will provide an insight into how players can help prevent shoulder problems altogether.

Understanding the shoulder

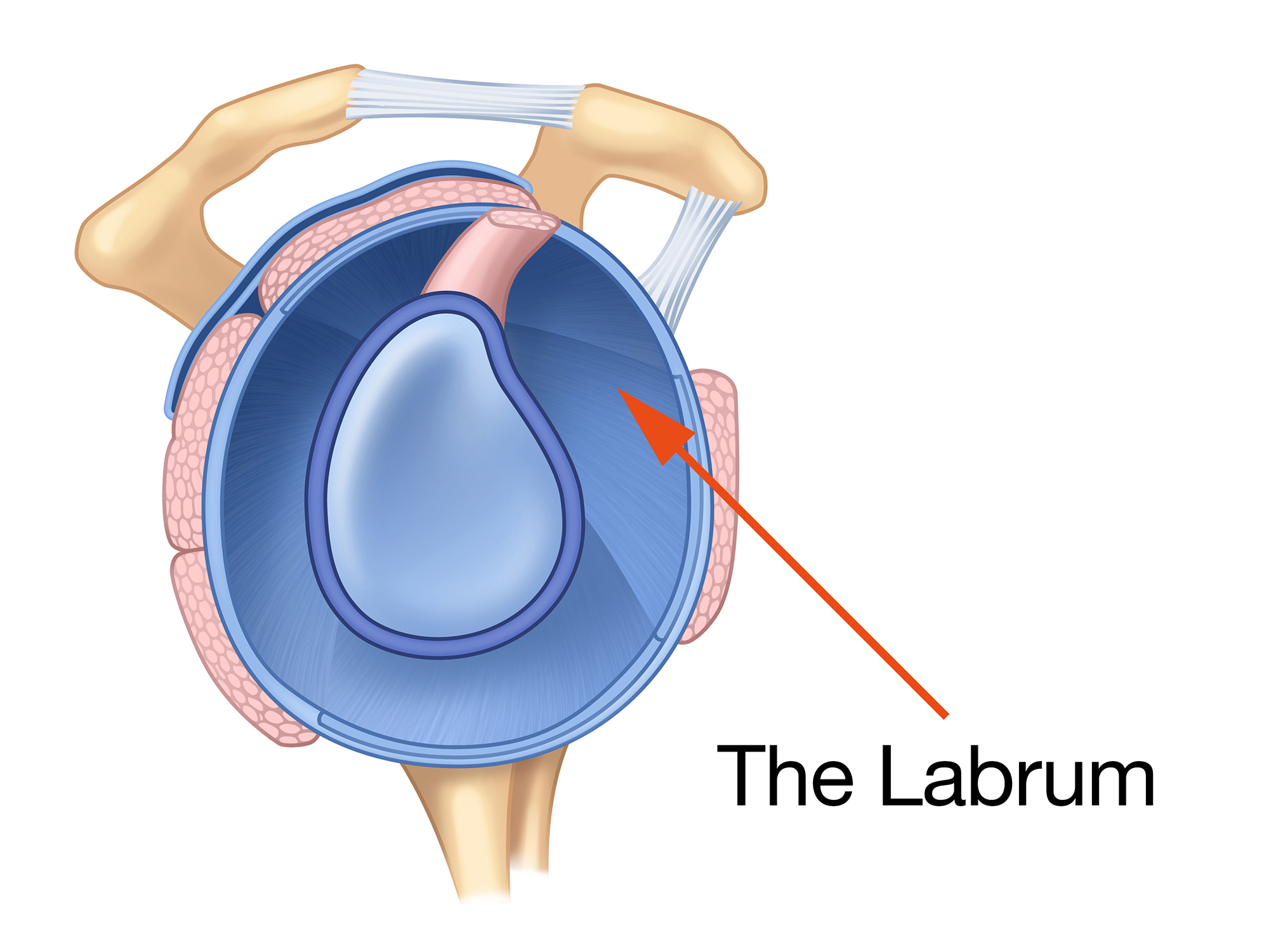

The shoulder is the most mobile joint in the body. It is reliant on static structures (bone, labrum, ligaments, capsule) and dynamic structures (muscular components) to provide stability. All these systems must work in harmony to give a balanced and high functioning athletic shoulder. The labrum is a small fibrous cartilaginous rim that circles and deepens the socket.

Figure 1

The shoulder is much less likely to dislocate posteriorly (out the back) however if a player gets a shunt that results in a tear of the posterior part of the labrum (back of the labrum), they sustain a reverse Bankart lesion (Figure 2 on the right). Alternatively, if a player suffers a traction type injury, such as landing with both arms stretched out in front they are more likely to traction part of the biceps tendon which attaches on to the top part of the labrum.

This is referred to as a SLAP lesion. Lesions can occur in isolation or together depending on the type of trauma. Often, the more complex the labral tear, the longer an athlete may be off from sport (varies from 14-30 weeks).

Figure 2

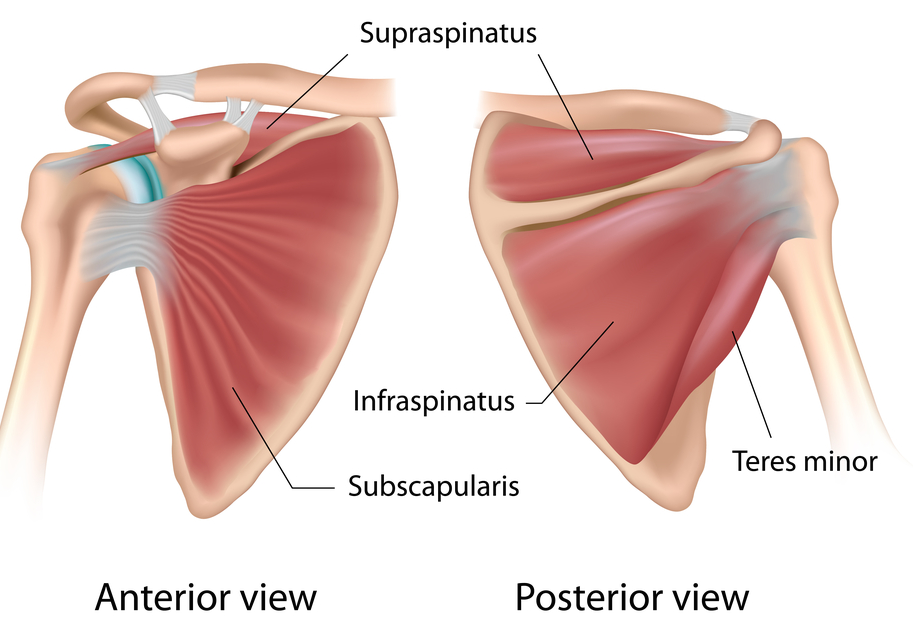

Surrounding the shoulder is a group of muscles called the rotator cuff. The rotator cuff is crucial in maintaining the stability of the shoulder (Figure 3). It is particularly important in vulnerable positions where the shoulder ligaments are less effective such as the tackle position. In recent years there has been a surge of exciting literature emerging on the function and role of the rotator cuff which is considerably improving how we rehabilitate the shoulder.

Surrounding the shoulder is a group of muscles called the rotator cuff. The rotator cuff is crucial in maintaining the stability of the shoulder (Figure 3). It is particularly important in vulnerable positions where the shoulder ligaments are less effective such as the tackle position. In recent years there has been a surge of exciting literature emerging on the function and role of the rotator cuff which is considerably improving how we rehabilitate the shoulder.The rotator cuff is small and hard to isolate and is often not necessarily targeted in the usual gym exercises such as the bench press, overhead press and rowing exercises. GAA players should consider adopting rotator cuff strengthening routines, coupled with shoulder blade exercises into their gym programmes for optimal shoulder function and control. |

Figure 3 Rotator Cuff

Shoulder stability is not solely reliant on the strength and control of the shoulder muscles. The quality of the shoulder function heavily depends on the function and power of the legs and trunk.

The kinetic chain (the interlinked relationship between segments of the body) generates the force and helps regulate load at the shoulder particularly in activities such as striking the ball in hurling. Weakness and altered coordination in the legs and trunk muscles can increase demands on the shoulder.

When rehabilitating the shoulder, whole-body movement should be assessed and treated as part of the overall problem.

What structures are injured in shoulder dislocation and when is surgery indicated?

Structural damage from shoulder dislocation can be grouped into two categories, major damage and minor damage. Major lesions can have a greater effect on the stability of the joint. These include a bony Bankart where some of the bone of the socket is damaged alongside the labrum, an injury where the labrum is peeled off alongside the fibrous tissues surrounding the bone (ALSPA lesion) and an injury that results in damage to the important ligaments of the shoulder. If a large rotator cuff tear occurs when the shoulder dislocates surgery is often required to repair the muscle. The timing of the injury is taken into account by the surgeons. If major damage is identified late into the season and a player is unable to return to play then surgery will often be considered at this stage.

Most stabilisations are performed through keyhole surgery. However, some high-risk groups for recurrent dislocation or patients who have dislocated in the past may require an open stabilising procedure called a Laterjet procedure.

What investigations are required?

It is common and safe practice post shoulder dislocation to have a check x-ray to ensure the shoulder has been relocated. X-rays are also useful to show if any bony damage has occurred. A routine x-ray will show if bony damage has occurred to the ball of the shoulder joint (Hill Sacs lesion). A special view can be ordered by a doctor or surgeon who can assess bony damage of the socket (bony Bankart).

To assess labral/capsular damage an MR Arthrogram or CT Arthrogram is the preferred choice. A plain MR scan can be useful to assess the integrity of the rotator cuff muscle however it is often not sensitive enough to assess the integrity of the labrum.

What are the risk factors for shoulder dislocation?

There are some factors we know can predispose athletes to shoulder instability. Athletes that have laxity in their shoulder, which refers to a ‘loose’ ligament/capsule complex, tend to have an excessive range of movement in the shoulder and are at higher risk of dislocating their shoulder. There are studies supporting that players in a contact sport who have poor isokinetic strength (the ability of a muscle to contract at a constant speed) of the shoulder may be at risk of injury. Athletes with asymmetry in their range of movement of the shoulder, particularly asymmetry in their rotational movements, are at greater risk. Impaired performance and/ or injury of the trunk and legs can increase the risk of a shoulder injury, particularly in overhead sports. There is some evidence suggesting that tackling fatigue in other contact sports such as rugby, leads to a decreased sense of shoulder joint position and this is a potential increase risk for injury.

Phase 1: Rest and recovery phase

Post-surgery, athletes are put in a sling with the time frame dictated by their surgeon, often depicted by the extent of injury and type of surgery. We work closely with our shoulder surgeons to establish ‘a safe zone’ where the athlete can start exercising without putting a strain on the repair. It is essential that the rehabilitation team work closely with the player’s surgeon to get the balance right. Strict immobilisation can result in rotator cuff inhibition and muscular atrophy. Closed chain exercises (where the hand is in contact with a surface) are frequently used in the protective phase. This type of exercise creates a relatively small joint movement, decreases joint shear and stimulates a sense of joint position while protecting the repair.

Phase 2: Progressive loading

Recruitment of the rotator cuff muscles is often affected post dislocation/post-surgery and a systematic approach is required to optimise function and facilitate return to play. Exercises should be prescribed that ensure timely recruitment, endurance and strength of the deep stabilising muscles. Emphasis is also put on rhythmic stabilisation exercises and perturbation training (exercises to improve reaction times) in this phase (Figure 4). This type of training helps the shoulder to develop force rapidly; a requirement for all parts of football and hurling. One of the key factors to success is to rehab in controlled positions of vulnerability that re-educate muscle synergy into all the positions the athlete requires.

Figure 4 Rhythmic Stabilisation Exercises and Perturbation Training

Phase 3: Return to play

The primary focus at this stage is to maintain muscle balance, maintain reactive stability and re-introduce graded return of exercises required for the athletes game e.g. ball skills, contact skills, drop and landing drills. The emphasis switches to increase the power (the ability to generate force quickly) of the shoulder muscles, which builds on the strength phase developed in the first two stages.

The average return to playtime can vary from 14 -30 weeks and is dependent on an athlete reaching set goals. Return to play is both player specific and surgery specific, taking into account the quality and type of surgical fixation achieved. ‘Return to play criteria’ is used to help ensure the safe return of an athlete to contact training. This often includes an assessment of the isokinetic strength of the shoulder. With the help of the strength and conditioning team, the aim is to ensure the athlete is globally fitter and stronger than their pre-injury presentation.

Shoulder dislocation is an injury risk in GAA sports and can result in a prolonged absence from the sport. However, with appropriate rehabilitation and exercise selection post-surgery it is possible to make a very efficient and successful return to sport.

| For further information on this please call +353 1 5262040 or email physio@sportssurgeryclinic.com |